Writing Fiction & Nonfiction Set in the Past

Official blog for historical novelist Nancy Bilyeau, author of the Joanna Stafford trilogy, Dreamland, The Blue, and The Orchid Hour

Saturday, November 22, 2025

Tudor History Podcasts: Hits and Misses on Elizabeth I

Sunday, November 9, 2025

Mary Jane Kelly: The Last Victim of Jack the Ripper?

By Nancy Bilyeau

“God forgive her,” some called out as the procession lumbered past.

Forgive her for what?

It was perhaps a welcome distraction from the horror.

|

| The stereotypical image of Jack the Ripper. In reality, to blend in on Dorset Street and the rest of Spitalfields, the murderer would have had to appear much less posh |

Although the police had interviewed at least 2,000 people, they had not zeroed in on the man responsible, the same one who may or may not have written taunting letters to the newspapers signed “Jack the Ripper.” There was some hope that the killing spree was over, since more than a month had passed. The Lord Mayor’s Show was an occasion to set aside fear and celebrate.

One person not hurrying to the parade was Jack McCarthy, landlord of many properties in Whitechapel occupied by the destitute, ranging from the respectable working poor to thieves, gamblers, hopeless alcoholics, and “Unfortunates,” the Victorian euphemism for prostitutes. As always, McCarthy had money on his mind. Around 10:30 am, McCarthy told his assistant, Thomas Bowyer, to try to collect the rent in arrears at №13 Miller’s Court, a ground-floor room on a narrow 20-foot-long cul-de-sac of Dorset Street.

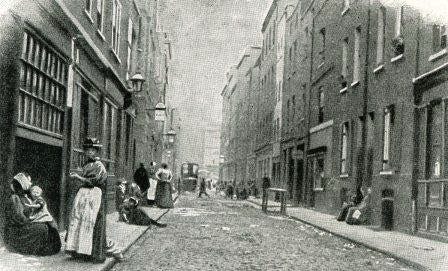

Even within Spitalfields, an overcrowded East End parish infamous for its poverty, crime, and filth, Dorset Street was in a class all its own. Part of the “wicked quarter mile,” it was a 130-yard-long street almost entirely occupied by common lodging houses and pubs. In 1901, the Daily Mail, under the headline “The Worst Street in London,” would publish an article saying, “…The lodging houses of Dorset Street and of the district around are the head centers of the shifting criminal population of London… the common thief, the pickpocket, the area meak, the man who robs with violence, the unconvicted murderer…”

As grim as these lodgings were, the alternative — “sleeping rough” — was worse. Many of the poor struggled daily to pay for their “doss house” bed. The September 8th victim of Jack the Ripper, 47-year-old Annie Chapman, was murdered while trying to earn enough money on the streets to pay the nightly charge at her common lodging house at 35 Dorset Street.

At 10:45 a.m., Thomas Bowyer knocked on the door of 13 Miller’s Court. In April of that year, a Billingsgate Market fish porter, Joseph Barnett, and his young companion, Mary Jane Kelly, had moved into the room, costing 4s/6d a week. It was 10-foot-square with two small windows, a bed, two tables, and a fireplace. In Spitalfields, this was a home better than the average.

But Barnett lost his job. He moved out after quarreling with Mary on October 30. She was living there alone, a common sight in the neighboring pubs, drinking with friends. Although she told those friends she was afraid of Jack the Ripper, Mary had turned to prostitution to support herself. It was not her first time earning her living as an “Unfortunate.”

|

| Pre-Raphaelite artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s painting “Found” |

On November 10th, the day after the murder, she sent a telegram to Prime Minister Lord Salisbury: “This new, most ghastly murder shows the absolute necessity for some very decided action. All these courts must be lit, & our detectives improved. They are not what they should be. You promised, when the 1st murders took place, to consult with your colleagues about it.” Three days later, Her Majesty sent her ideas to the Home Secretary of what the detectives should focus on, including “The murderer’s clothes must be saturated with blood and must be kept somewhere!”

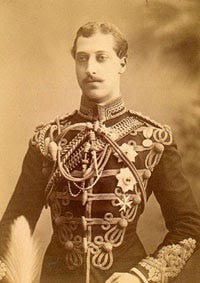

As for the persistent association of Queen Victoria’s grandson, Prince Albert Victor Christian Edward, the Duke of Clarence, to the public and Prince Eddy to friends, with the crimes, the prince was unquestionably not prowling the East End at the time of the murders. Documentation has placed him far away from London. On the night of the “double event,” Prince Eddy was at Balmoral. To account for this inconvenient fact, subsequent theories have his doctor or trusted aide killing off prostitutes to cover up a secret marriage or as vengeance for syphilis. These are fantasies.

“She said she was born in Limerick and went when very young to Wales. She did not say how long she lived there, but that she came to London about four years ago. Her Father’s name was John Kelly, a gaffer or a foreman in an ironworks in Carnarvonshire or Carmarthen. She said she had one sister, who was respectable, who traveled from market place to market place. This sister was very fond of her. There were six brothers in London and one in the Army. One of them was named Henry. I never saw her brothers. She said she was married when very young to a collier in Wales. I think the name was Davis or Davies. She said she lived with him until he was killed in an explosion.

After her husband’s death she went to Cardiff to a cousin. She was following a bad life with her cousin, who, as I often told her, was her downfall. She was in a gay house [brothel] in the West End, but in what part she did not say. A gentleman came there to her and asked her if she would like to go to France… She did not remain long…”

A friend confirmed that Mary said she was originally from Ireland. She talked of receiving letters from a beloved mother and hoping to reunite with her and live there.

Nonetheless, in the 137 years since her death, no fact about Mary Jane Kelly’s background has been verified. Despite the efforts of many Ripper scholars, there are no records of her birth, marriage, or residency in Ireland, Wales, or France. No member of her family attended her funeral or came forward after her murder; no one could find evidence of the young husband’s life or death. There is not a trace of her to be found before she came to London. This was not the case for the other four women, who were thought to have been killed by the Ripper. Researchers have records of birth and marriage, employment, and even a wedding photo of one woman.

It is possible that Mary Jane Kelly used a false name the entire time Barnett and their friends knew her and invented all the details and names of family and husband. If so, will anyone ever discover her real identity? Because she was the last agreed-upon victim of Jack the Ripper, the youngest, the most horribly murdered and the most mysterious, she maintains an inescapable grip on the imagination of those obsessed with the crimes, unsolved to this day.

On Monday, November 19th, 1888, the woman known as Mary Jane Kelly was buried at St. Patrick’s Catholic Cemetery in Leytonstone. Barnett and her friends could not pay for her funeral; the expenses were met by a sexton of Shoreditch. Thousands attended the six-mile-long procession, some straining to touch her coffin. Men removed their hats; women called out, “God forgive her.” Two mourning carriages followed, carrying Barnett and five women friends. The coffin was carried to an open grave listed as №16, Row 67.

Scenes of my childhood arise before my gaze

Bringing recollections of bygone happy days.

When down in the meadows in childhood I would roam,

No one’s left to cheer me now within that good old home,

Father and Mother, they’d have pass’d away;

Sister and brother, now lay beneath the clay.

But while life does remain to cheer me, I’ll retain

This small violet I pluck’d from mother’s grave.

Only a violet I pluck’d when but a boy,

And oft’ time when I’m sad at heart this flow’r has giv’n me joy;

So whole life does remain in memoriam I’ll retain,

This small violet I pluck’d from mother’s grave.

Well I remember my dear old mother’s smile,

As she used to free me when I returned from toil,

Always knitting in the old arm chair,

Father used to sit and read for all us children there,

But now all is silent around the good old home;

They all have left me in sorrow here to roam,

But while life does remain, in memoriam I’ll retain

This small violet I pluck’d from mother’s grave.

Saturday, November 1, 2025

Interview: Jillian Forsberg of 'The Porcelain Menagerie'

I was intrigued to hear about the new novel by Jillian Forsberg, titled The Porcelain Menagerie, and even more so to learn it is set in the eighteenth century! In researching and writing The Blue, I delved into the tumultuous--even violent--history of porcelain creation in Europe, once inventors had "broken" the secret of the Chinese formulas.

I was lucky enough to read an advance copy of Jillian's novel and loved it. Here's a plot description: In a world where ambition is as fragile as porcelain, two lives are shaped by a king's dangerous obsessions. In 18th-century Dresden, the dangerous whims of King Augustus the Strong shape the court and the lives of those held captive, both people and animals.

Now the novel is out and winning rave reviews everywhere. I caught up with Jillian to ask her a few questions:

Nancy Bilyeau: You and I are both drawn to the history of porcelain when creating historical fiction. Why does it fascinate you?

Jillian Forsberg: Art history has always been interesting to me, but the creation of porcelain is truly an intriguing story — I love secrets, drama, and beauty, and porcelain encompasses all of those things. From the Chinese makers who perfected it to the Europeans who tried and failed and tried again to copy it, there’s such humanity in the process. In China, from one step to the next is the product of community, and in Europe, it always inspires me to find stories of reliance when the early makers failed so many times and just kept at it. It’s amazing, too, to see the differences in art that are considered wildly successful from different parts of the world: some look amazing, and some look downright grotesque.

NB: What makes the 18th century an exciting setting for a narrative?

JF: Well, I think I’m biased! My master’s thesis is set in the 18th century, and therefore, a lot of my mental energy was spent in that time period. Those 100 years for me have always been delicious because of the Age of Enlightenment, the expansion of curiosity, and then, toward the end of the century, upheavals and revolutions all over the world. One of my favorite things is a good museum gallery, and the 18th century produced some of the finest artifacts and collections of any time period. The ultra-wealthy sought out collections of all kinds of things, and it really was a testament to how the 1% lived. But below the shimmering surface of fine goods, the middle class was finding its footing… the thread through the 18th century is change, beauty, and endings. That makes for quite an exciting historical fiction setting!

NB: I find Augustus the Strong pretty mind-blowing as monarchs go. What were the most surprising things you learned about him?

JF: He truly is. I think I was truly surprised that even with my formal education, I had never heard of him. He would have been sorely disappointed in that! The man was almost a caricature as far as kings go — over the top, outlandish, boisterous, and relentless. But he didn’t really DO anything. The latest biography published about him, just last fall, is literally called Augustus the Strong: A Study in Artistic Greatness and Political Fiasco. He tried his best to be memorable, but unfortunately, what was most recorded was his rumored 300+ bastard children, terrible addiction to blood sport, chaining artists to the floors of their studios, and, my personal favorite, ripping horseshoes in half in front of a crowd. The man was unbelievable. A perfect fictional subject, a quite imperfect king.

To learn more about Jillian Forsberg, go to her website.

To order The Porcelain Menagerie, click here.

Tuesday, August 12, 2025

Giveaway of The Heiress of Northanger Abbey & Kickstarter FAQs

Muse Books, the publisher of my next novel, is offering a special giveaway of The Heiress of Northanger Abbey.

The Heiress of Northanger Abbey is part of "Once Upon a Gothic," a four-book set: The other classics with sequels or retellings will be Frankenstein, Phantom of the Opera, and Dracula.

My novel can be ordered individually or as part of the quartet. This is all an initiative happening on Kickstarter. Fiction sold on Kickstarter is a new path to publishing fiction that's gaining in popularity. Because of its newness, people have a lot of questions. I figured my website blog would be a good place to answer the questions I'm fielding.

Please follow this campaign on Kickstarter. Signing up to follow it does not obligate you to buy anything! If you are curious about this publishing journey, following the campaign is the best way to gain information. And if you are a reader, we hope very much you will want to support our breaking free from traditional paths to do something different and creative. Thank you so much!

Sign up here: Click "Notify Me on Launch" It's FREE :)

Thursday, July 3, 2025

Limited-Time Deal: 'The Blue' Is Free

I'm thrilled to let people know that they can download my novel, THE BLUE, for free until July 5. It's the first book in my Genevieve Planche series.

Joffe Books set a three-day deal on the ebook of THE BLUE, coordinating with BookBub on a promotion.

Here's the Publishers Weekly review from the time of its publication in 2018:

Genevieve Planché, the appealing 24-year-old narrator of this intriguing thriller from Bilyeau (The Crown), longs to be a painter at a time, 1759, when “female sensibilities” are considered “too delicate for art.” Reluctantly, she accepts a job as a decorator at the Derby Porcelain Works, but before setting off from her London home, she’s approached by dashing Sir Gabriel Courtenay, who asks her to spy on the new chemist at the factory, Thomas Sturbridge, who has “created an entirely new shade of blue.” In exchange for this treachery, she’s promised enough money to set herself up as a painter in Venice. After agreeing to this scheme, she comes to realize that the quest for the new blue can alter the destiny of a king and create works of awesome beauty but also lead to kidnapping, betrayal, and murder. Fascinating details include glimpses of the newly opened British Museum, a Christmas party at the home of William Hogarth, and Madame de Pompadour’s residence at Versailles. Historical fans will be well satisfied.

I was fortunate enough to win endorsements for THE BLUE from some wonderful authors:

Thursday, April 17, 2025

My Novel 'The Versailles Formula' Is on Sale

The day has arrived!

The Versailles Formula, my eighth historical novel, is available in paperback and ebook format in North America, the United Kingdom, and Australia. I've created a suspenseful story rich with atmospheric detail that I hope will plunge you deep into mid-18th-century England and France.

Reviews:

‘In Genevieve Planché, Bilyeau has created a wonderfully wilful woman: as smart as she is sensitive, as brave as she is bold. Compelling to read . . . This is a series going from strength to strength.’ Kate Braithwaite, author of The Scandalous Life of Nancy Randolph

To order:

Wednesday, April 16, 2025

What Other Authors Say About 'The Versailles Formula'

With one day left before the official publication of The Versailles Formula, I would love to share the early reviews and endorsements from other novelists. Some are historical novelists, some are thriller writers, and some are historical mystery scribes. I deeply appreciate the time they took to read it and wanted to share the response to the book from my peers.

"Nancy Bilyeau's Versailles Formula is the continuing compelling adventure of whip-smart and determined heroine Genevieve Planché. It’s replete with spies, political intrigue, gorgeous gothic manor houses, romance, impeccably researched history—and the shocking history of the color blue."

--Susan Elia MacNeal, New York Times bestselling author of the Maggie Hope series

"A plucky heroine, intriguing mystery, and rich, well-researched historical background. Nancy Bilyeau has found the winning formula!"

--Eva Stachniak, author of The School of Mirrors

"Nancy Bilyeau has done it again. It is a masterful work which weaves great characters not to mention a plot that Poe himself would love. The story unfolds through the eyes of the protagonist and we see a treacherous world where nothing is as it seems. When we enter the Gothic world of Sir Horace Walpole then the reader treads a thrilling path which keeps you on the edge of your seat."

--Griff Hosker. author of An Officer and a Gentleman

"The excitement and action ramp up steadily, and Bilyeau's exquisite pacing will have you wanting to binge the novel in one sitting. Part espionage novel, part intriguing look at the historical importance of art and the porcelain industry to 18th-century diplomacy, The Versailles Formula is a riveting and deftly written tale that will keep you up much too late at night, for all the right reasons."

-- Paulette Kennedy, author of The Artist of Blackberry Grange

"Bilyeau gives the reader a fabulous tour of 18th-century Paris from its convents and opera houses to the louche masked balls of the aristocracy. Genevieve is a complicated, highly intelligent character who never falls into the dull predictability of the "spirited woman ahead of her time" tropes. The ending leaves the possibility open for another Genevieve Planche novel, and I very much look forward!"

-- Mariah Fredericks, author of The Wharton Plot

"In Genevieve Planché, Bilyeau has created a wonderfully wilful woman: as smart as she is sensitive, as brave as she is bold. Compelling to read . . . This is a series going from strength to strength."

--Kate Braithwaite, author of The Scandalous Life of Nancy Randolph

"An indomitable artist turned spy heroine on a near impossible mission. A color of blue so seductive that men will kill for it and countries will go to the brink of war. A star-crossed love, as delicious as it is forbidden. Thoroughly researched and exquisitely wrought, The Versailles Formula has all the ingredients of a rollicking, riveting historical mystery must-read!"

-- Hope C. Tarr, author of Irish Eyes and Stardust

"What impressed me the most is her gift for detailed description. When Genevieve lands in Paris to begin her dangerous mission, we can see the narrow streets with their buildings that 'sagged towards each other, nearly touching.' Inside the Comedie Française, we smell the 'thick, intoxicating swirl of perfume, a hothouse of human flowers blooming all at once.' And we can laugh at the absurdity of the nobility in their white silk socks, jeweled shoes, and heads covered in wigs that 'resemble sparkling beehives.' The Versailles Formula is a master class in the lost art of description, and I loved it for that."

--Jodi Daynard, author of A Transcontinental Affair

"With action-packed scenes to rival the classic The Scarlet Pimpernel, Nancy Bilyeau's excellent third book in the Genevieve Planché series, The Versailles Formula, solicits page-turning suspense until the very end. Reader, be ready for the world outside of reading this book to disappear."

-- Susan Wands, author of Magician and Fool

"Nancy Bilyeau's engaging protagonist, Genevieve Planché, returns in an undercover mission to 18th-century Paris, where she risks her life to unearth a secret that could reignite war between England and France. But Genevieve’s quest is as personal as it is political — Cracks have begun to form in her once-happy marriage, and she finds herself drawn to the man assigned to be her partner in France. With a cast of real and fictional figures, prose as smooth as French silk, and breathtaking twists, The Versailles Formula is exactly the book any lover of historical fiction would want to have in their hands right now."

"Thanks to the depth of Bilyeau’s craft, readers will share Genevieve’s tension and fear as she races through settings from rough, working-class Southwark to glittering Versailles. As Genevieve’s heart races, so will yours. If you like your mystery with twisty, dark history, The Versailles Formula is for you."

-- Sophie Perinot, author of Medicis Daughter

"Sumptuous and deeply engaging, Nancy Bilyeau's Versailles Formula is a gorgeously written adventure . . . brimming with mystery, beauty, romance, and history's most fascinating luminaries."

"The action takes place in England and France, castles and cemeteries and chateaux, grand ballrooms, sinister prisons, and cloistered convents. Historical figures flit through, from Horace Walpole, the father of the Gothic novel, to the Marquis de Sade, who lived one. The Versailles Formula is Bilyeau at her best, a classic tale of mystery and intrigue that only lacks a cameo from a dueling D'Artagnan to make my life complete. If you've read the first two books in the series, this is one you've been eagerly awaiting. If you haven't, this is a hellacious introduction."

--Timothy Miller, author of The Strange Case of the Pharaoh's Heart.

"The Versailles Formula takes readers on a fascinating journey to eighteenth-century England and France, where vicious aristocrats play a deadly game of forgery and espionage . . . Nancy Bilyeau treats us to another tale full of intrigue and delightful historical details."

-- Mark Alpert, bestselling author of The Doomsday Show

%20Out%20now.png)