By Nancy Bilyeau

Yet just before leaving England, King Henry had a distinctly unromantic encounter with another woman. He met face-to-face with a female who was roughly Anne Boleyn’s age but was not a courtier’s daughter possessing style and Continental polish. Elizabeth Barton, humbly born, was a Benedictine nun of the Priory of St. Sepulchre, in Canterbury.

Sister Elizabeth was, like many people, loyal to the king’s estranged wife, Queen Catherine of Aragon, and did not want him to marry Anne Boleyn. But unlike the vast majority of English men and women, she was determined to do something about it.

According to a statement taken later, Sister Barton told Henry VIII “she had knowledge by revelation from God that God was highly displeased with our said Sovereign Lord…and in case he desisted not from his proceedings in the said divorce and separation but pursued the same and married again, that then within one month after such marriage he should no longer be king of this realm, and in the reputation of Almighty God should not be king one day nor one hour, and that he should die a villain’s death…”

Henry VIII’s response to Sister Elizabeth’s threat in 1532 is unknown. But less than two years later, she would be dead, the only nun executed in the reign of the king. She had no trial. The methods that the king and his ministers used to persecute and condemn her for treason set the pattern to be used on others that Henry VIII wanted to destroy. She was the first of the retaliation deaths.

Anne Boleyn

Although she presented a serious obstacle to Henry VIII’s marriage to Anne Boleyn, and was later used as an instrument to bring down the highest-ranking of the king’s critics, Cardinal John Fisher, Sister Elizabeth Barton does not appear in hardly any historical fiction (or TV series or films) taking place in the 1530s except for Wolf Hall in which she is mocked as an attention seeker. She is described dismissively in most works of nonfiction. Tudor historian Geoffrey Elton called her “that deluded prophetess” and, more recently, Geoffrey Moorhouse described her as “the somewhat deranged and visionary serving maid.”

What has undoubtedly diminished the legacy of Sister Elizabeth is the Tudor government’s propaganda machine. A long manuscript was written by Barton’s confessor; a printed tract of her life widely circulated throughout England; an illuminated letter was produced by a monk – all of these documents were destroyed. We cannot read them today. The accepted chroniclers of the 16th century, all of them Protestant, are our sources of her life story, along with a few references made by foreign ambassadors. It is hard to glimpse a view of the human being through the distortions.

Sister Elizabeth’s saga bears some resemblance to Joan of Arc’s, a century earlier. Joan was a peasant who experienced visions. Elizabeth was a servant who fell seriously ill in 1525, lost consciousness, and when she came to, made references to the health of a boy also ill whose fate she could not have had knowledge of. She shared visions that called for veneration of God. Word spread, and those living in Kent began to make pilgrimages. She is supposed to have proclaimed prophecies and performed miracles but we don’t know the details. “She told plainly of divers things done at the church and other places where she was not present, which nevertheless she seemed most likely to behold as if it were with her own eye.”

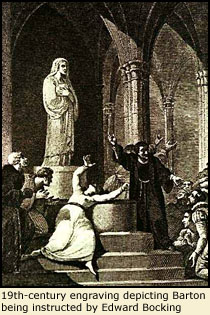

Church authorities interviewed Elizabeth early on and proclaimed her a genuine mystic. They were not eager to anoint seers; quite the opposite. She was examined rigorously by a series of priests, monks and bishops, all of them on the outlook for “trickery.” The Archbishop of Canterbury William Warham personally saw her and said her visions were genuine. In a letter he described her as a “well -disposed and virtuous woman.” Elizabeth entered the nunnery of St. Sepulchre to be either protected or controlled, depending on how you look at it. “The Holy Maid of Kent” made appearances at a church in Canterbury, and at one point up to 2,000 people jostled to surround her.

What is beyond question is that Elizabeth Barton had some sort of chronic illness for the rest of her life, whether it was physical, neurological or psychiatric. Her visions often came to her while she appeared to be suffering painful fits, writhing on the floor, or in a trance.

Much later, the next archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer, known for his skepticism and dislike of superstition, wrote this eyewitness account of Elizabeth’s fit: “Then there was a voice heard speaking within her belly, as if it had been in a tun, her lips not greatly moving, she all that while continuing in a trance. The which voice, when it told everything of the joys of heaven, it spake so sweetly and heavenly that every man was ravished with the hearing thereof. And contrary, when it told anything of hell, it spake so horribly and terribly that it put the hearers in great fear.” In our modern minds, these bizarre breakdowns in health would hurt her credibility. But in the medieval era, holy women were often traumatically ill at the time of experiencing visions.

Elizabeth Barton became famous before Henry VIII launched his famous quest for a divorce from Catherine of Aragon. She already had enemies, though. Elizabeth called for obedience to pious works and traditional worship, tenets that were under attack in a Germany transformed by Martin Luther. All of Europe was in turmoil over the spreading religious reform.

What is beyond question is that Elizabeth Barton had some sort of chronic illness for the rest of her life, whether it was physical, neurological or psychiatric. Her visions often came to her while she appeared to be suffering painful fits, writhing on the floor, or in a trance.

Much later, the next archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer, known for his skepticism and dislike of superstition, wrote this eyewitness account of Elizabeth’s fit: “Then there was a voice heard speaking within her belly, as if it had been in a tun, her lips not greatly moving, she all that while continuing in a trance. The which voice, when it told everything of the joys of heaven, it spake so sweetly and heavenly that every man was ravished with the hearing thereof. And contrary, when it told anything of hell, it spake so horribly and terribly that it put the hearers in great fear.” In our modern minds, these bizarre breakdowns in health would hurt her credibility. But in the medieval era, holy women were often traumatically ill at the time of experiencing visions.

Elizabeth Barton became famous before Henry VIII launched his famous quest for a divorce from Catherine of Aragon. She already had enemies, though. Elizabeth called for obedience to pious works and traditional worship, tenets that were under attack in a Germany transformed by Martin Luther. All of Europe was in turmoil over the spreading religious reform.

Henry VIII derided Luther in writing and was rewarded by the pope’s proclaiming him “Defender of the Faith.” What’s hard for us to grasp is that, before 1527, it was unthinkable to the world that the king of England would discard his longtime queen or that he would break with Rome. He was an orthodox ruler, an obedient son of the church. Reformer and scholar William Tyndale, living in exile, called Elizabeth a “false, dissembling harlot.” (Protestant opponents often accused Barton of sexual misconduct, without any foundation whatsoever.) Since Henry VIII opposed, hunted down, persecuted and finally killed Tyndale--who died in the flames crying, “Lord, open the king of England’s eyes”—Henry Tudor and Sister Elizabeth Barton were on the same side.

Until they weren’t.

The "Holy Maid” did not publicly prophesy against the king. She repeatedly tried to warn him against his course of action, first to his ministers and finally to him in person. In 1528, Barton told Cardinal Wolsey that God commanded her to tell him that if he furthered the king’s marriage to Anne Boleyn he would be “utterly destroyed.” (Wolsey was disgraced after he failed to get the king his divorce and died on way to trial.) John Fisher, the churchman who supported Catherine of Aragon, wept with joy when he heard Sister Elizabeth’s visions. Sir Thomas More was more cautious, telling her that her words were “reckless.” Catherine of Aragon herself was careful to never meet or corresponded with Elizabeth, her champion. The embattled queen could see the danger that Elizabeth and her many followers seemed oblivious to.

|

| "The Maid of Kent" |

Although he knew of her activities, Henry VIII did not move against the nun for a long time. During one stage he tried to pacify her, even to bribe her. He offered to make her an abbess of her own priory. She refused the offer.

Elizabeth’s fame and influence continued to grow. She met with foreign ambassadors and the papal representative in England. She wrote letters to the pope, urging him to stop the king from divorcing. She had secret meetings with English nobility, including Gertrude Courtenay, the marchioness of Exeter, wife to the king’s first cousin. Collections of Sister Elizabeth’s prophecies were printed and widely circulated.

Barton herself said that she prevented Henry VIII from marrying Anne Boleyn in Calais, as he was rumored to be planning to do. When they did marry, it was in great secret.

It was widely known that Sister Elizabeth predicted if Henry VIII wed Anne, he would soon lose his kingdom and die. After several months had passed and he was very much alive, the king moved against her. Barton and her most devoted followers were arrested and harshly questioned in late 1533. There is no proof of torture, although another woman, Anne Askew, would be racked nearly to death for her religious “crimes” a decade later.

Whatever the means of persuasion, Elizabeth Barton supposedly told her captors what they wanted to hear. She recanted her visions and said, Cranmer wrote, “all was feigned of her own imagination, only to satisfy the minds of them which resorted unto her, and to obtain worldly praise.” This did not save her. Henry VIII directed Parliament to pass a special act condemning her for treason without a hearing. The punishment was death.

Elizabeth Barton, around 30 years of age, was hanged and then beheaded on April 20, 1534, her head fixed on Tower Bridge, the only woman known to be so displayed after death. The head of Cardinal Fisher was later mounted as a warning to others when he was executed for treason, in part because he was charged with conspiring with Elizabeth Barton. Five men were executed with her the same day, all of them priests, monks or parsons who had believed in her prophecies.

This same spring of 1534 was when Henry VIII demanded that the church and the people follow him into schism with Rome. The terms of the Act of Succession were proclaimed everywhere. People were warned that if they said or wrote anything against the king’s marriage to Anne Boleyn or his lawful heirs by her, they would be guilty of treason, punishable by death.

All the records of Sister Elizabeth’s confession come from the crown. In 1536, Queen Anne Boleyn would also be turned into a nonperson after execution: letters, documents, portraits destroyed. Because her daughter grew up to be a great queen, Anne’s reputation was restored. This never happened with Elizabeth Barton. She is usually dismissed as a tool of religious plotters, or mentally ill. The possibility that this was a young woman who felt compelled to have a say in the affairs of the kingdom, and possessed the courage to try to interfere, is rarely acknowledged.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

Nancy Bilyeau is the author of the Tudor mystery trilogy The Crown, The Chalice and The Tapestry, on sale in North America, the United Kingdom, German, Spain, and Russia. The main character is Sister Joanna Stafford, a Dominican novice.