By Nancy Bilyeau

It's exciting to set a historical novel in a time period that's rarely chosen by other writers.

And ... it's frightening too.

When I decided to write a thriller set during the competitive rage for porcelain, the 18th century jumped into play. The famous Meissen Porcelain began operation in 1708 and dominated Europe until Sevres Porcelain overtook it mid-century. But the English factories were contenders as well.

It's been called the long century and one thing is certainly clear: the 18th century was dominated by wars fought among the great European powers. France and England clashed again and again, beginning in the reign of Queen Anne, the last Stuart monarch, and continuing right through to the end with the Napoleonic wars.

A smart editor friend of mine, Daryl Chen, told me that she thinks historical fiction benefits from being set during a war. I agree with Daryl, and after researching the timeline of porcelain competition in Europe, I decided the Seven Years War was perfect. It began in 1756 and ended in 1763.

I don't know the percentage breakdown for the wars chosen by historical novelists being published in the 21st century, but I'd wager a guess it is 70 percent are set during World War Two, smaller numbers for World War One or the American or English Civil War. The Seven Years War? It might come in at .05 percent: my book, The Blue. :)

Which is too bad, because the Seven Years War was a dramatic, high-stakes, game-changing conflict that raged in Europe, the Americas, West Africa, India, and the Philippines. Its resolution changed the world significantly. It left such resentment in the hearts of the losers, the kingdom of France, that when colonists rebelled against England in America in 1775, the French, driven out of North America in the 1760s, were eager to send money and officers over the Atlantic to do damage to their enemy. Many believe that by doing so, France set up the conditions for its own revolution in 1789. There were many, many reverberations from the Seven Years War.

|

| The famous Battle of Warburg, 1760 |

I never regretted choosing this time period for my fourth novel. But it was lonely. When I was finished writing The Blue and was going through the editing stage, in a moment of curiosity, I plugged into Google "Movies set during Seven Years War."

A very short list popped up, but I smiled when I saw one title: The Last of the Mohicans. Of course! I saw the film in a theater when it came out in 1992 and I loved it. The Seven Years War is called the French and Indian War in North America, and the movie tells a story set amid that conflict.

In 1826, James Fenimore Cooper published his novel set in the upstate New York wilderness, detailing the transport of the two daughters of Colonel Munro, Alice and Cora, from Albany to Fort William Henry. Guarding the women during the journey are frontiersman Hawkeye and his loyal Mohican friends and adopted family Chingachgook and Uncas as well as a British officer, Major Duncan Heyward. After being betrayed by the renegade brave Magua, the party reaches the fort, only to lose it in a French siege. In the violence that follows, some of it along a cliff in the New York mountains, Cora, Uncas, and Magua are all killed.

In his film, director Michael Mann made huge changes in the plot. The thrust of the film is a romance: Hawkeye and Cora are the ones who fall in love, upsetting Major Heyward, who wished to marry Cora. After the surrender of the fort, betrayal, and flight, Major Heyward is burned to death by order of a Huron tribal leader, and Cora's sister Alice, Uncas, and Magua die.

It was the romance between Hawkeye, played by Daniel Day Lewis, and Cora, played by Madeleine Stowe, that captivated audiences. In particular this scene became immortal:

I decided to watch the film again recently, to see if there were any common themes between my novel The Blue and The Last of the Mohicans. I wasn't sure there would be. Different continents, for one thing. And Mohicans is a story paying tribute to the struggle over America, fought deep in the wilderness. My novel is about the frenzy for fine porcelain that preoccupied Europe regardless of the war, and how a young female painter's quest to discover the most beautiful shade of blue became tangled with objections of that war.

I was, quite simply, stunned by the beauty of this film. The love story is powerful, no doubt, but I swooned to the costumes, the sets, sophisticated cinematography, and the musical score that has taken its place as one of the best of the last 50 years.

In the opening of the film, cinematography, music, and action fuse in an elk hunt that is unforgettable:

In his first major Hollywood film, Daniel Day Lewis as Hawkeye carries the film, but I found the performances of Wes Studi as Magua, Russell Means as Chingachgook, and Stephen Waddington as Major Heyward (a difficult part) nothing less than amazing.

It is a bit easy to miss in such a romantic, gorgeous film, but there is a serious political theme to the film, one that resonated with me. As the story begins, the British are trying to recruit colonial settlers in New York to serve in a militia, a proposition that Hawkeye has nothing but scorn for. This puts him on a collision course with Major Heyward, a stiff officer obsessed with rank and victory who is appalled when a general tells the colonists that they'll be allowed to leave the militia should they hear their farms are being attacked by the French-led Native Americans. Once they reach Fort William Henry, the news of just such attacks--the enemy murdering helpless women and children--leads the colonialists to insist they be allowed to go to their families. But the British renege and refuse to let them go. "Those considerations are subordinate to the interests of the Crown," declares Colonel Munro. Hawkeye helps the Americans sneak away, but then he stays behind to be with Cora, who he loves, and is arrested for sedition.

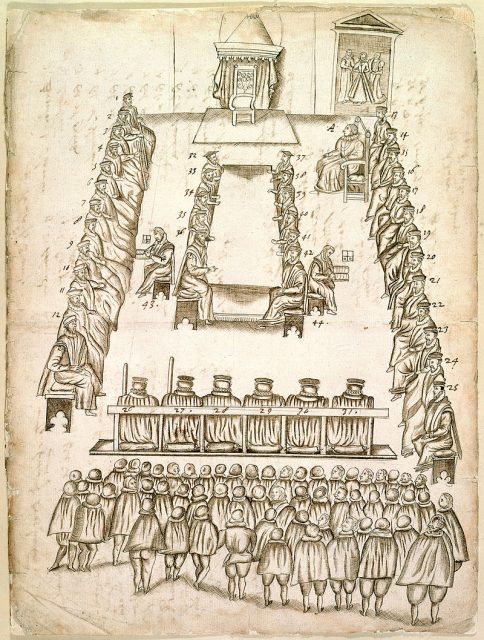

|

| Hawkeye is arrested for sedition |

After the French blow holes in the fort with their superior guns, the English surrender and retreat. Although the sequence of multiple battles and escapes that takes up the last one-third of the film is for some fans their favorite part of the movie, I disagree. The theme of whether a person should stand up for their rights and personal freedom is lost among the running, attacking, and burning. And a weakly established romance between Uncas and Alice Monroe suddenly guides the narrative.

|

| Magua is killed in the finale, but Chingachgook has lost his son. He is now the "last" of the Mohicans, |

But fighting for your freedom is still the deepest message of the film. And that dawning awareness of a person's right to determine their own fate amid a meaningless and brutal war between superpowers is an important part of my novel The Blue as well. The ideas sparked by the Enlightenment cannot be extinguished. The chemist who is creating the color blue, Thomas Sturbridge, puts science above politics. He is unimpressed by the war, and his ideals spark important changes within my main character, Genevieve.

In a Hollywood now dominated by cartoons and superheroes, it's sad to think about the narrative ambition and beauty of Last of the Mohicans. Happily, the film is admired and written about by others than me. I found a great story on its 25-year anniversary.

And because no one can be unmoved by the song "The Kiss," I leave you with this clip:

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Blue is an editors pick by Goodreads and Bookbub. Publishers Weekly said: "historical fans will be well satisfied." To learn more, go here.