By Nancy Bilyeau

One spring day in 1539, twenty-six women were forced to leave their home— the only home most had known for their entire adult lives. The women were nuns of the Dominican Order of Dartford Priory, in Kent. The relentless dissolution of the monasteries had finally reached their convent door. Having no choice, Prioress Joan Vane turned the priory over to King Henry VIII, who had broken from Rome.

What the women would do with their lives now was unclear. Because Dartford Priory surrendered to rather than defied the crown, some monies were provided. Lord Privy Seal Thomas Cromwell, the architect of the dissolution that poured over a million pounds into the royal treasury, had devised a pension plan for the displaced monks, friars and nuns. According to John Russell Stowe’s History and Antiquities of Dartford, published in 1844, Prioress Joan received “66 pounds, 13 shillings per annum.” She left Dartford and was not heard from again—it’s thought she lived with a brother.

Sister Elizabeth Exmewe, a younger, less important nun, received a pension of “100 shillings per annum.” This was the amount that most Dartford nuns received. The roaring inflation of the 1540s meant that such a pension would probably not be enough to live on after a few years—but there was never a question of its being adjusted.

Some of the thousands of monks and friars who were turned out of their monasteries in the 1530s became priests or teachers or apothecaries. But nuns—roughly 1,900 of them at the time of the Dissolution--did not have such options. “Those who had relatives sought asylum in the bosom of their own family,” wrote Stowe with 19th century floridity. Marriage was not an option. In 1539, the most conservative noble, the Duke of Norfolk, introduced to Parliament “the Act of Six Articles,” which forbade ex-nuns and monks from marrying. The act, which had the approval of Henry VIII, became law. The king did not want nuns in the priory but he did not want them to marry either. There was literally no place for them in England.

Sisters who could afford it immigrated to Catholic countries to search for priories that would take them in. Others lacking family support sank into poverty. Eustace Chapuys, the Spanish ambassador, wrote: “It is a lamentable thing to see a legion of monks and nuns who have been chased from their monasteries wandering miserably hither and thither seeking means to live; and several honest men have told me that what with monks, nuns, and persons dependent on the monasteries suppressed, there were over 20,000 who knew not how to live.”

Such wandering through England would not be the fate of Elizabeth Exmewe. Enough is known of her life from various sources to gain a picture of a determined woman.

Dartford Priory, founded by Edward III, drew women from the gentry and aristocracy, even one from royalty. Princess Bridget Plantagenet, youngest sister of Elizabeth of York, was promised to Dartford as a baby. She lived there from childhood until her death in 1517. Elizabeth Exmewe was typical of most of the other nuns—she was the daughter of a gentleman, Sir Thomas Exmewe. He was a goldsmith and “merchant adventurer,” serving as Lord Mayor of London.

It was common for brothers and sisters to enter monastic life together, though at separate places. Elizabeth’s brother, William Exmewe, was a Carthusian monk and respected scholar of Greek and Latin at the London Charterhouse. He was also one of the monks who in 1535 refused to sign the Oath of Supremacy to Henry VIII, despite intense pressure. The king had broken from the Pope because he could not get a divorce from Catherine of Aragon and marry Anne Boleyn. Once the king became head of the Church of England, it was imperative that all monks shift their loyalty to him. But Exmewe would not compromise his beliefs, and he was punished with a horrifying death: He was hanged, disemboweled while still alive and quartered.

No nun in England was executed besides Sister Elizabeth Barton, a Benedictine who prophesied against the king’s marriage to Anne Boleyn. Barton was arrested, tortured, tried, and hanged for it. Elizabeth Exmewe did not publicly criticize the king nor seek martyrdom. Four years after the death of her brother, she was turned out from Dartford Priory.

Historians studying the dissolution have noted a remarkable fact: in several cases, nuns attempted to live together in small groups after being forced from their priories. They were determined to continue their vocations, in whatever way they could. Elizabeth Exmewe shared a home in Walsingham with another ex-nun of Dartford. “They were Catholic women of honest conversation,” said one contemporary account. A half-dozen other Dartford refugees tried to live under one roof closer to Dartford. Meanwhile, Henry VIII had their priory demolished. He built a luxurious manor house on the rubble of the Dominican Order, although he’s not believed to have ever slept there. It became the home of his fourth wife, Anne of Cleves, after he divorced her in disgust in 1540.

Following the reign of Henry’s Protestant son, Edward VI, his Catholic daughter, Mary I, took the throne in 1553. Mary re-formed several religious communities as she struggled to turn back time in England and restore the “True Faith.” Elizabeth Exmewe and six other ex-nuns successfully petitioned Queen Mary to re-create their Dominican community at Dartford, which was vacant after the death of Anne of Cleves. They moved into the manor house, built on the home they left 14 years earlier, with two chaplains. The convent life they loved flourished again: the sisters spent their days praying, singing and chanting; gardening; embroidering; and studying.

But the restoration didn’t last long. When Mary died and her Protestant half-sister took the throne, one of Elizabeth’s goals was extinguishing the monastic flames. In 1559 Elizabeth’s first Reformation Parliament repressed all the re-founded convents and confiscated the land.

And so the Dartford nuns were ejected again, this time with no pensions. Mary’s widower, King Philip of Spain, heard of their plight, and paid for a ship to convey the nuns of Dartford and Syon Abbey to Antwerp, in the Low Countries. Paul Lee, in his book Nunneries, Learning and Spirituality in Late Medieval Society, has charted the sisters’ poignant journey after leaving their native land.

After a few months, a new home was secured for them. For the next ten years Elizabeth Exmewe lived “in the poor Dutch Dominican nunnery at Leliendal, near Zierikzee on the western shore of the bleak island of Schouwen in Zeeland.” Several of the English nuns were entering their eighties, with Elizabeth being the youngest. All suffered from illness and near poverty. The Duchess of Parma, hearing of their hardships, sent an envoy to the Dartford nuns. He wrote: “I certainly found them extremely badly lodged. This monastery is very poor and very badly built…. I find that these are the most elderly of the religious and the most infirm, and it seems that they are more than half dead. “ Despite his dire observances, the nuns themselves expressed pride in their convent. Their leader, Prioress Elizabeth Croessner, wrote a letter to the new pope, Pius IV, saying they strove to remain faithful to their vows and were interested in new recruits!

In the 1560s the nuns died, one by one, leaving only Elizabeth Exmewe and her prioress, Elizabeth Croessner. Destitute, the pair moved to Bruges and found another convent. They lived through a bout of religious wars, with Calvinists marching through the streets.

The onetime prioress of Dartford, Elizabeth Croessner, died in 1577. Now Elizabeth Exmewe, the daughter of a Lord Mayor and the sister of a Carthusian martyr, was the only one left of her Order. In 1585, she, too, perished in Bruges and was buried by Dominican friars with all honors. Elizabeth Exmewe is believed to have lived to 76 years of age.

---------------------------------------------------------

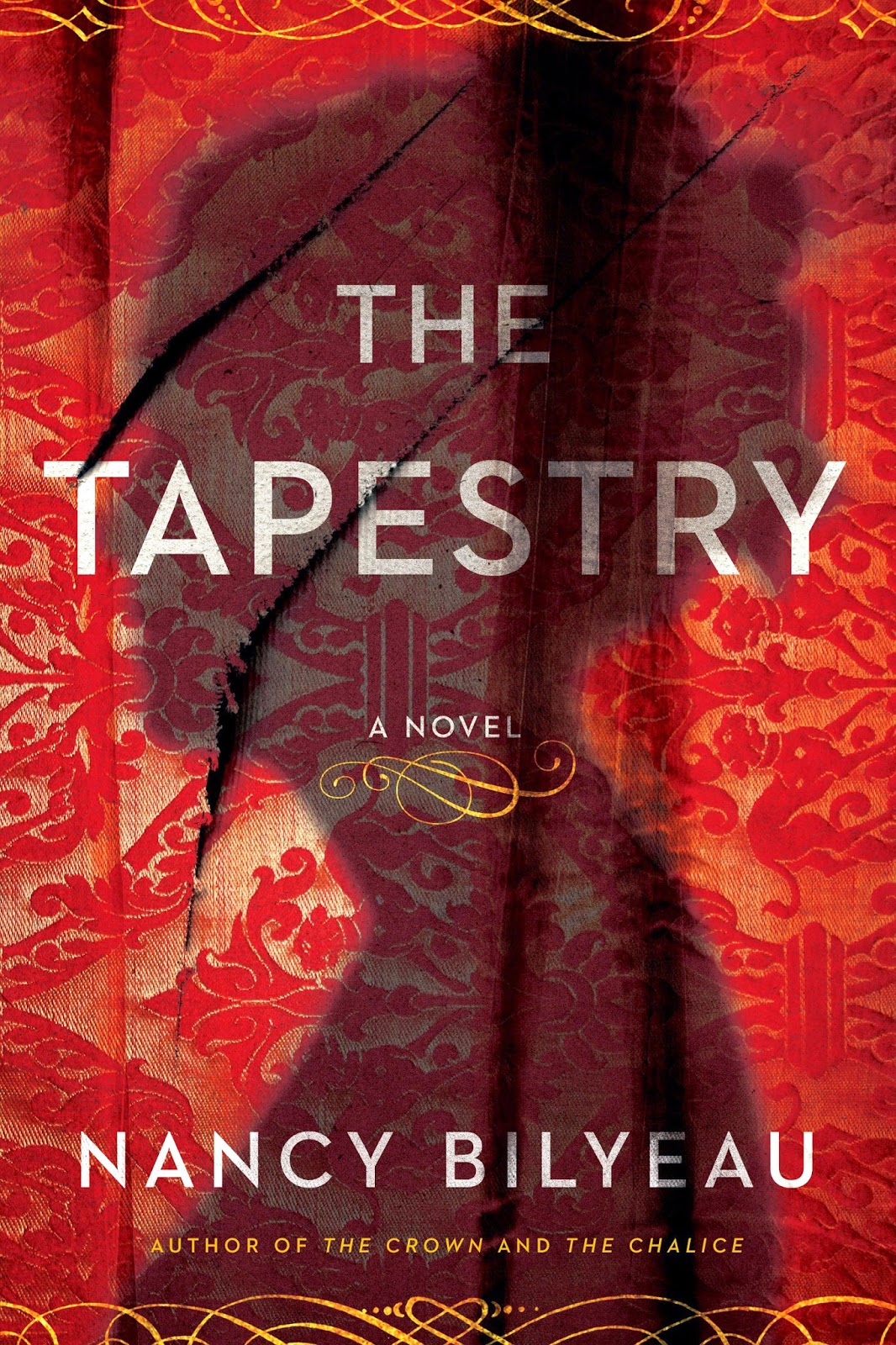

Nancy Bilyeau is the author of a trilogy of historical thrillers published by Simon & Schuster in North America and nine foreign countries. The main character is a Dominican novice. The Crown, published in 2012, was an "Oprah" pick. The Chalice, published in 2013, won the award for Best Historical Mystery last year. The Tapestry will be published on March 24, 2015.

Anyone interested in obtaining a review copy, please contact Nancy here.